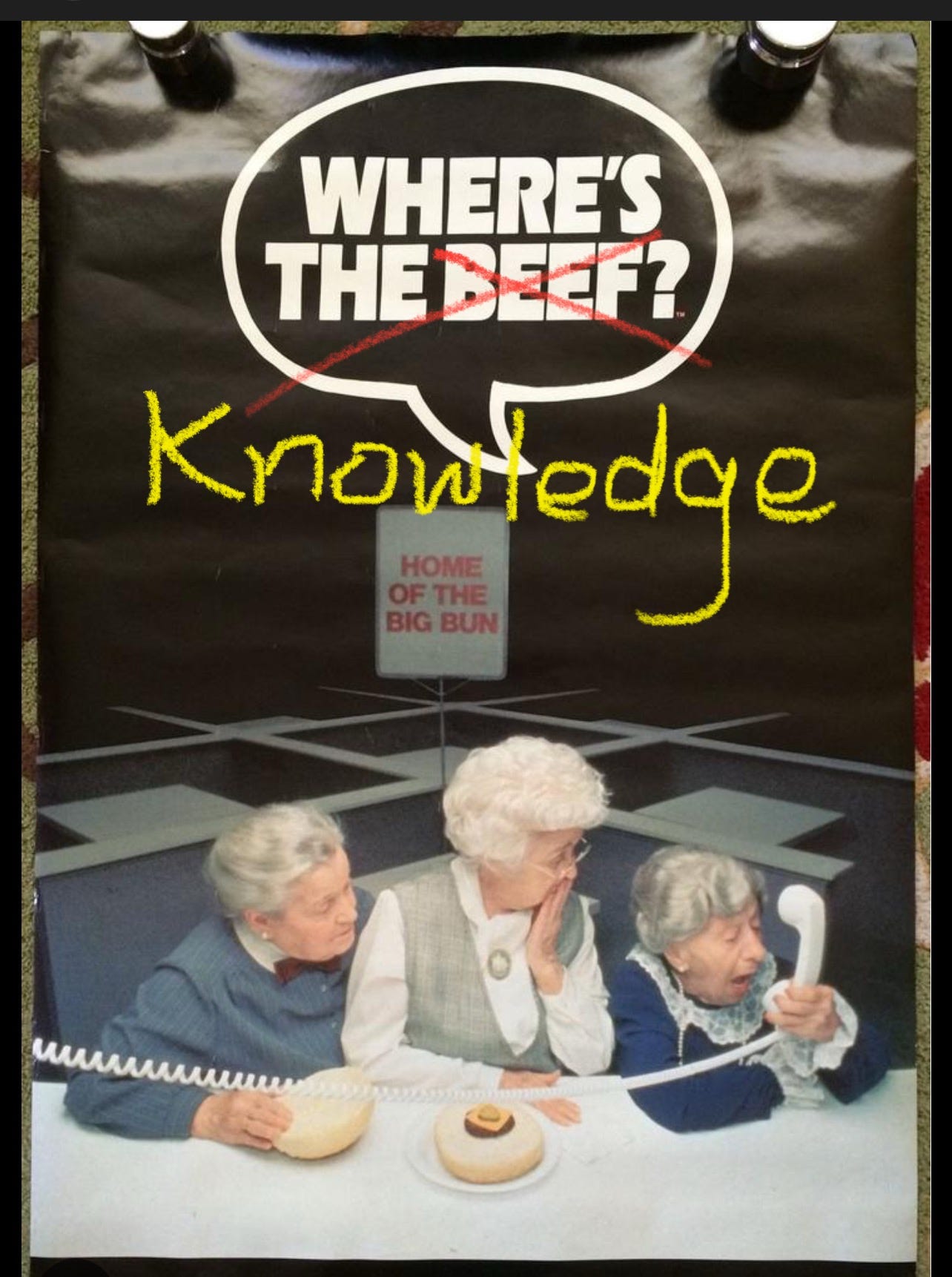

Knowledge is the Missing Subject

Elementary schools devote very little time to social studies and science instruction. I am certain there are many reasons why, but I think the biggest reason is that they want more time for reading and math. Our assessment scores in reading and math are not great (far from it in some cases), which has led to heightened concerns about how we’re teaching and learning to read. The great irony, though, is that by prioritizing learning to read, we’ve essentially cut off a main source that develops reading comprehension: knowledge of the world.

In all the needed focus on the “science of reading” we’ve neglected the purpose of reading: to know more about words, the world, ourselves, and others.

(As a side note and a focus of a later post, this study found that instruction in social studies had a larger positive effect on reading growth than instruction in ELA: https://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/view-article-2021-02/se-85012132.pdf)

The Common Core State Standards (2010) defined a person as ready for college and/or a career in English language arts as someone who demonstrates independence, builds strong content knowledge, responds to the varying demands (is flexible in their thinking and application of knowledge), comprehends and critiques, values evidence, uses technologies proficiently, and understands other perspectives and cultures.

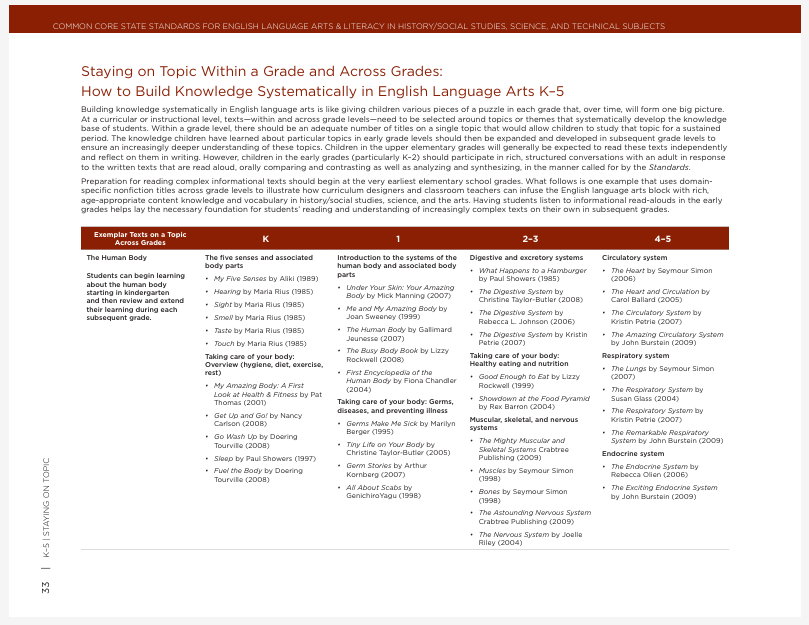

The Common Core State Standards also included this (page 32):

© Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights reserved.

While some of you might be aware of these aspects of the standards, I’m betting that many of you didn’t dig into the front matter and extras. And, if any of you recall the “shifts” that were suggested with the standards in ELA, one of the shifts was a call for “Building knowledge through content-rich nonfiction.” There was a backlash at the time. Many folks cried out that this was an end to literary texts in ELA. But according to a 2022 study by Kristin Smith Conradi, Craig A. Young, and Jane Core Yatzeck and quoted by Dr. Molly Ness in a podcast: “94% of early childhood teachers choose fiction texts as their read-alouds.” So clearly keeping literary texts front and center in ELA seems not to be an issue.

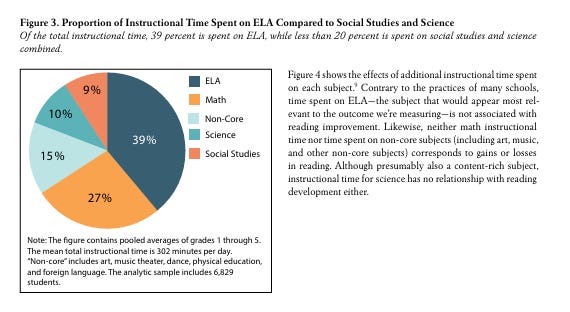

Despite these pushes, school continue to carve out less and less time for building knowledge. Here are some startling stats:

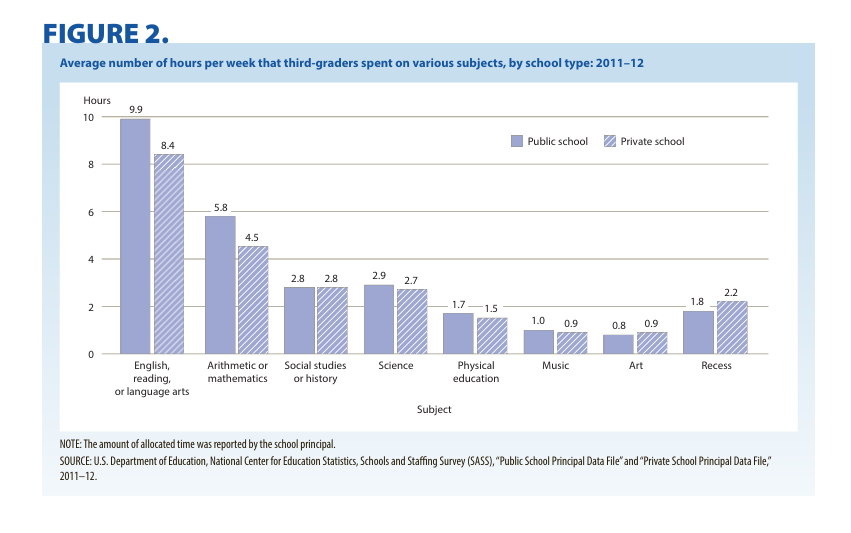

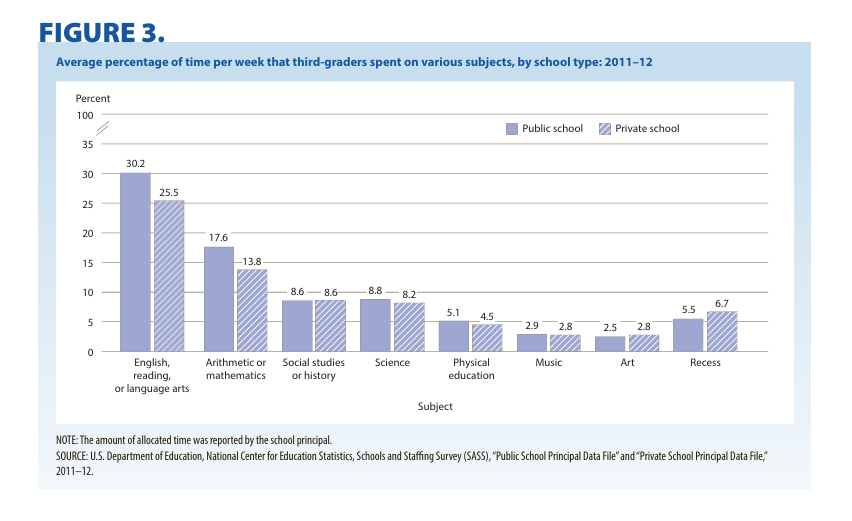

From a February 2017 National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) report on instructional time:

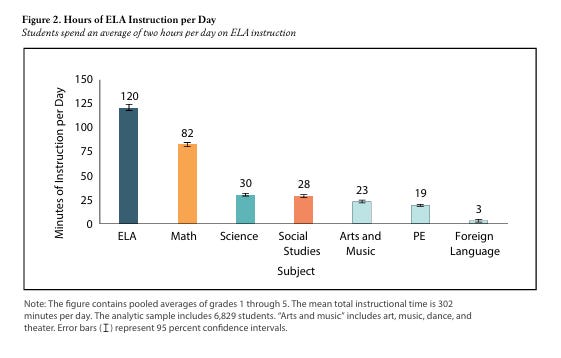

From an EdWeek article: “Social Studies and Science Get Short Shrift in Elementary Schools. Why That Matters,” by Sarah Schwartz:

“In a 2018 national survey, K-3 teachers said they spent a daily average of 89 minutes on English/language arts and 57 minutes on math but only 18 minutes on science and 16 on social studies.”

From “How Social Studies Improved Elementary Literacy” by Adam Tyner and Sarah Kabourek in Social Education 85(1), pp. 32-29, ©2021 National Council for the Social Studies

From a 2023 RAND Report: “The Missing Infrastructure for Elementary (K-5) Social Studies Instruction”:

“Only half of elementary principals said their schools had adopted published curriculum materials to support kindergarten through grade 5 (K–5) social studies instruction.”

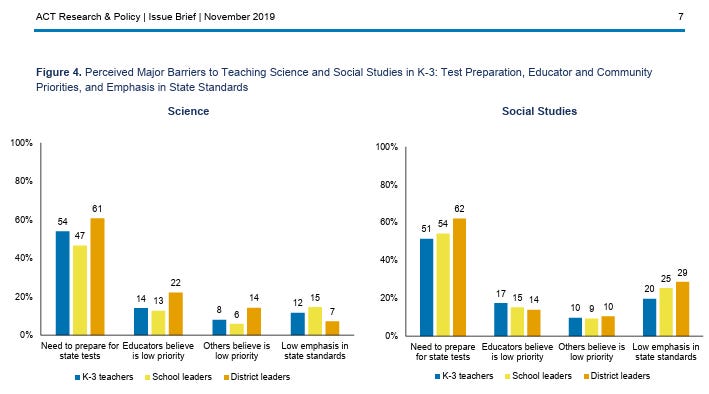

From “Educators’ Beliefs about Teaching Science and Social Studies in K-3” by Chrys Dougherty, PhD, and Raeal Moore, PhD from ACT Research & Policy Issue Brief, November 2019

The ACT issue brief linked above also identifies four possible benefits for teaching science and social studies in early elementary classes:

Yet, as Natalie Wexler points out in this Forbes article, teachers largely still spend more time on ELA and math, even though they generally believe that history and science are important.

So, elementary-aged kids spend very little time learning science and social studies instruction in school. Then, when they come home, where are they spending their time? Are they reading informational texts about science and history topics or are they playing video games and watching videos on YouTube or TikTok? Are they having rich, knowledge-building experiences visiting museums or other cultural institutions or local landmarks or parks?

When and where are elementary-aged children learning science and social studies?

We often assume this learning is happening somewhere, but it isn’t. Knowledge is the missing subject.

And yet, knowledge is the fuel for reading and thinking. I go into more detail on the role of knowledge in our cognitive processes in “Reading Misunderstood.” Here’s the gist: Reading comprehension and critical thinking aren't generic skills. They are built on what we know. Without spending time thoughtfully and actively building knowledge in elementary schools when kids are most curious and interested in figuring out words and the world, children miss out on the knowledge necessary to engage in the more complex thinking and reading they are expected to do in later grades. That gap in knowledge is a gap in reading and a gap in thinking.

Let’s fix this!

Join us in The Knowledge Builders Club for Families, and use our free curriculum to build knowledge with your kids, whether in a traditional school setting or at home.

A secret worth knowing: The best way to help kids become strong readers is to help them build a rich knowledge of words, the world, and themselves.

A question worth pursuing: If knowledge fuels comprehension, why do our schools keep cutting back on science and social studies?

Next steps worth taking:

Try our free knowledge-building curriculum with your kids and join The Knowledge Builders Club for Families to get more resources and support!

Balance bedtime books and sprinkle in some nonfiction about science or social studies topics.

Review these other resources on knowledge:

Share this post with someone who is interested in building knowledge with their kids.