Louisiana's Curriculum Story

How Common Curriculum Leads to Learning Interoperability

Interoperability is the ability to share data or information across different and disconnected systems. In technology, interoperability is enabled by standards. Think Bluetooth. The existence of that standard allows you to share music from your phone to a speaker. They just work together. Without Bluetooth, getting your music from your phone to your speaker might be a huge undertaking. Prior to Bluetooth and digital audio files, we would play music via a CD or tape. It would be recorded in a studio, distributed on a CD, and then played by a CD player.

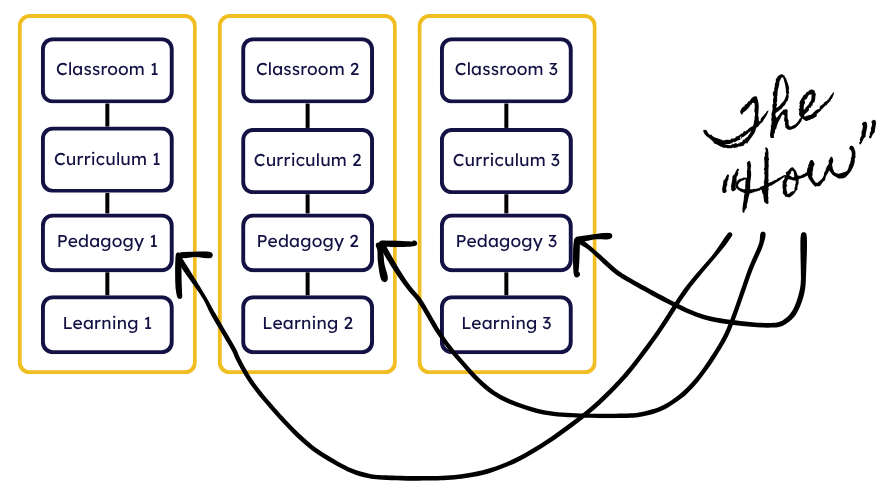

In the case of learning, interoperability is the alignment of content and experiences across classrooms so that students and teachers can share and collaborate. In a traditional school setting where there is no interoperability, teachers have their own curriculum and ways of implementing it. That’s their pedagogy. They manage the flow of a classroom differently and it impacts learning. Think about the start of a school year. How many parents wait anxiously to learn which teacher(s) their child will have that year? It makes a difference, and this is a problem if we want ALL children to learn.

This variation reveals a deeper systems problem: without a shared starting point, teachers cannot meaningfully align practice. Content standards have long been thought of as that point of intersection and alignment, but they largely do not result in common learning experiences, especially in ELA where the standards do not identify content. While an often used solution is to train teachers in general methods and approaches and hope they figure out how to apply that to their subject area, that leaves the most difficult part, the actual implementation with students, to an inexperienced teacher. Another often used solution is to employ coaches to work side-by-side with teachers in the classroom. But that’s a very costly and time-intensive solution.

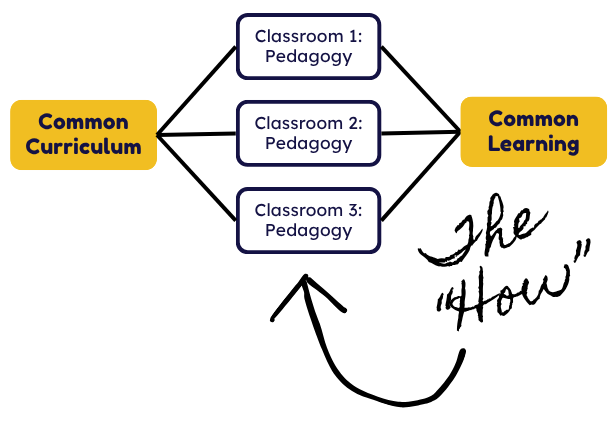

What neither of these solutions recognizes is that what teachers are teaching affects how they teach it. Thinking about this from a systems perspective, if teachers are starting from a common place, a common curriculum, then the “how” becomes much more focused.

Traditional Systems

Common Curriculum

Common curriculum creates an opportunity for learning interoperability. When that common curriculum is also high quality, it raises initial expectations schoolwide. Having shared curriculum can result in shared content and goals across classrooms, which can lead to true teacher collaboration if it is encouraged and supported. Shared effort can also lead to greater gains.

Becoming a Teacher

When I was learning to be a teacher, my main question in methods class was, “How do you design curriculum?” And surprisingly, no one ever had an answer. I got to peek at what teachers developed, but no one ever could share how they developed it. The best advice I received was to make one amazing unit a year. Then after 4-6 years, I’d have an amazing curriculum. This advice was the most realistic in terms of design—start small, get quick wins, and scale from there—and it also allowed me to focus on the process of implementation.

When I started teaching, I was obsessed with engineering the perfect curriculum. I would spend all summer perfecting the text selection, the order, the big ideas, the questions, and the learning activities. I would show up at school each day up to two hours before to make copies and organize everything. Then, when the curriculum would “go live,” that’s when the real work began! Sometimes it would run itself, but most often I had to observe and adjust in the moment. I would document those changes for updates the next year. And every now and then a lesson would totally flop, but that was rare, especially as I tested and improved them each year.

We team taught. We met daily to discuss students and how they were doing. We used the time to call parents or meet with students. We also co-planned. The expectation was that the same thing would be taught in each subject no matter the teacher. And if a math test happened on a Tuesday, then we wouldn’t test on ELA on Tuesday. It allowed for coordination to create a more reasonable, quality learning experience for each student in the school. When I was a middle school student, we were in teams. When I then taught middle school, we were in teams. I don’t know any other way of doing middle school. So it was a great shock to me when I started designing learning experiences for the state of Louisiana and realized that teachers did not expect common curriculum nor teach in a way that acknowledged all kids in a school were their kids.

Louisiana’s Comprehensive Curriculum

Prior to leaving the classroom for the Louisiana Department of Education, I was expected to teach the Louisiana Comprehensive Curriculum, which came out in 2005. The state had released “grade-level expectations” or GLEs as part of the accountability plan and then developed the Comprehensive Curriculum to demonstrate how to achieve those GLEs. In English language arts, the Comprehensive Curriculum was a list of unit themes based on genres (e.g., short story, mystery, non-fiction) and sample activities. The curriculum was woefully insufficient. Not only did it not actually explain what to teach and when, but the sample activities were all “fun” activities with a lot of arts and crafts (e.g., create a drawing of a character of your choice to show their motivations) and not much learning.

Following the release of the Comprehensive Curriculum, state policy required each district to create or adopt a curriculum aligned to the GLEs. But given that textbook adoption wasn’t for another few years and districts had to make a decision within a few days of the state sharing the policy, my district, as did many others, adopted the Comprehensive Curriculum as their curriculum. Our textbook then became a source for text access and ready-made assessments.

The Comprehensive Curriculum sat on a shelf in my classroom. While I generally followed the themes so that if someone asked I could demonstrate that we were following it, my adoption of the curriculum was loose at best. Many districts created “pacing guides,” and expected teachers to follow the guides religiously. Thankfully my district stayed away from that curriculum edict. Even as we created our own curriculum, what we taught in our school was still common.

The Shift to Common Core

When the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) came around, I was already at the Louisiana Department of Education. At first, I was very hesitant to develop curriculum for the whole state. I didn’t think the approach was good given my experience with the Comprehensive Curriculum. Teachers felt forced to use something that wasn’t working for them. They blamed a lack of choice and creativity.

When we adopted the CCSS as a state and declared the Comprehensive Curriculum and all textbooks as not aligned to the new standards, though, we sent districts into a tailspin. They immediately asked us how they were supposed to change their practice for a changing statewide assessment when we were giving them no tools nor support. I began to realize that the issue wasn’t the concept of common curriculum, it was a lack of high-quality, usable curricula.

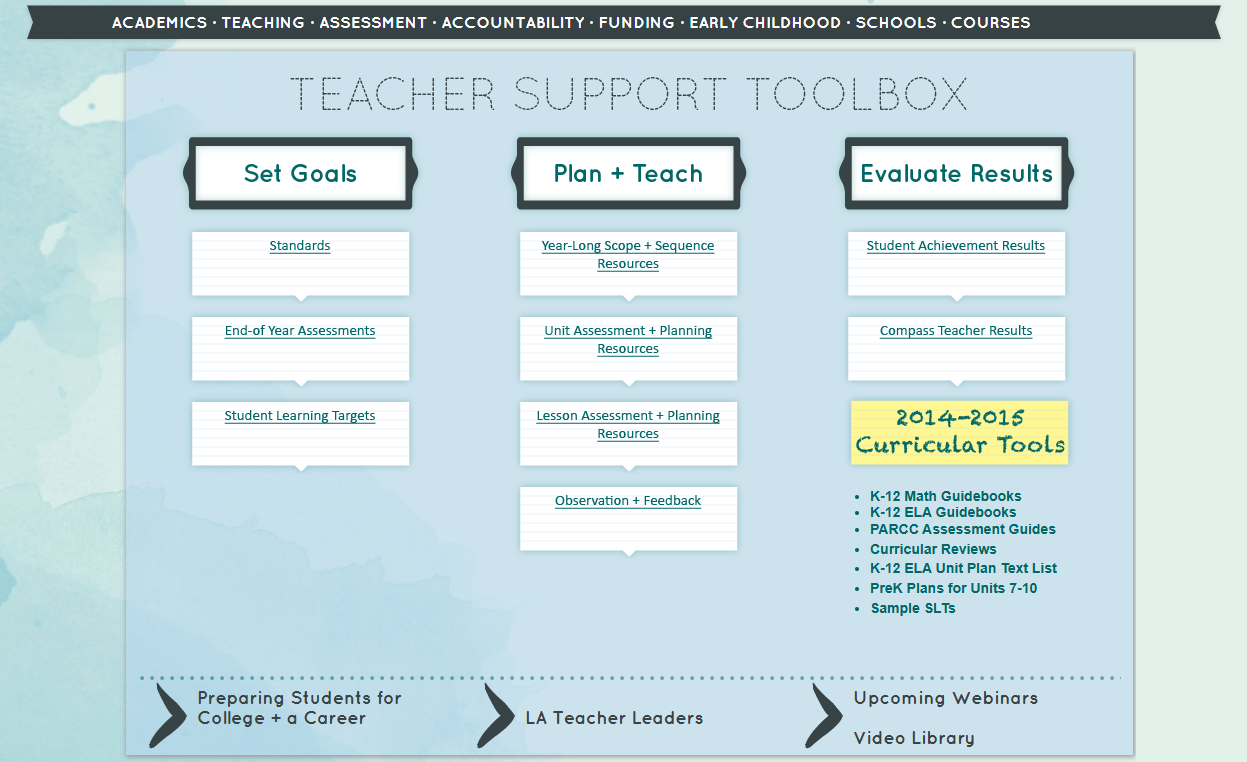

So, in early 2013, we created year-long guides (e.g., 6 text sets per grade) and then hosted our very first Teacher Leader Summit in Lafayette, Louisiana. I presented a single unit plan that I designed for each grade with teacher leader advisor help and the room stared at me blankly. They said, “This is great, but it’s not enough. How do you expect me to implement this? And what about the rest of the year?”

So, we went back to work—a group of energetic teachers and I—to develop a full year of unit plans for each grade. That became ELA Guidebooks 1.0.

Once we created the curriculum, we then spent a lot of time with teachers convincing them that not only is a common curriculum good, but it’s something they should want. Many teachers were burned by the Comprehensive Curriculum and distrustful of the quality of materials the state produced, so we also spent a lot of time on how to implement. We pushed hard against pacing guides and pushed hard toward focusing on learning and results: What conditions do you need to create to enable the kind of learning we want? (This was the “shifts” in ELA.) What do student responses look and sound like? How will you know if students are learning? What kinds of questions are quality? How do you have an academic discussion? How do you look at trends rather than individual scores at a single moment in time?

With each engagement we learned more about what teachers needed to implement the curriculum and so we added and adjusted the curriculum accordingly. When I left in 2018, we were on ELA Guidebooks 3.0.

The Comprehensive Curriculum laid the groundwork for the ELA Guidebooks. The Comprehensive Curriculum established the idea that there needed to be alignment and connection among all the parts of the educational system. The ELA Guidebooks then raised the expectations for what and how students would learn.

We acknowledged that teachers needed tools to do their job. “Failing by Design: How We Make Teaching Too Hard for Mere Mortals“ by Robert Pondiscio became a must read in our trainings. We asked a lot of teachers already and then to suggest that they would also have to figure out what to teach seemed unnecessary and unwise. Couple that with the fact that many were never taught how to create curriculum, so they relied on textbooks or whatever the state provided. Prior to the ELA Guidebooks, what teachers had available to them was embarrassingly poor quality.

We provided them with a clear pathway and model of what we expected for them to do their job well. Teachers appreciated the support. It wasn’t a guessing game.

We created a high-quality, knowledge-building curriculum that was also highly usable from the start. We gave them “sensible defaults.” Just like when you open Microsoft Word and can just start typing, we created a curriculum from which you can just start teaching. Of course, like with Word where you can adjust fonts and font sizes, the ELA Guidebooks were also customizable if a more experienced teacher wanted to make changes.

We treated the curriculum like a recipe. While novice teachers may need to follow the recipe as written at first, as they become skilled with it, they will likely internalize the steps and expectations of results and can adjust to accomplish an even better outcome. If we knew the learning we wanted children to have, why not be clear about what that looks and sounds like so teachers have clarity and consensus about how to get there?

We made the right thing the easy thing. We didn’t expect teachers to have to create a bunch of handouts; we gave them those. We didn’t expect them to have to interpret or unpack standards to figure out what kids need to produce to demonstrate learning; we shared exemplar responses.

High-quality, common curriculum creates a more coherent experience for teachers and students. This coherence creates learning interoperability. Children experience more consistent expectations, methods, approaches, and content, which results in greater chances for connections across classrooms. Those connections are where learning happens.

Notably, after I wrote my first draft of this post, Rod Naquin (a former teacher leader advisor and current high school teacher in Louisiana) shared a post he wrote in October about coherence and its benefits. If “coherence” interests you, his post is worth reading:

Read more about our curriculum work and lessons learned:

1. User experience matters and teachers are the main curriculum users, not students:

2. Focusing on quick wins and iterating to scale (the whole, make one great unit and grow from there advice) secures buy-in, and is less costly and allows for greater quality content. We learned and adjusted so we didn’t waste efforts and build the wrong thing to start:

3. Teachers and students benefit from learning interoperability and coherence because it allows for collaboration and shared efforts. We’re seeing this in the results in Louisiana and teachers are talking about the changes: https://knowledgematterscampaign.org/post/school-tour-visit/ouachita-parish-schools/

This! This is what ELA teachers NEED! We have so often been left to interpret such broad expectations with little guidance for expected outcomes other than good scores on standardized tests.

This is so excellent, Whitney! Love the graphics.