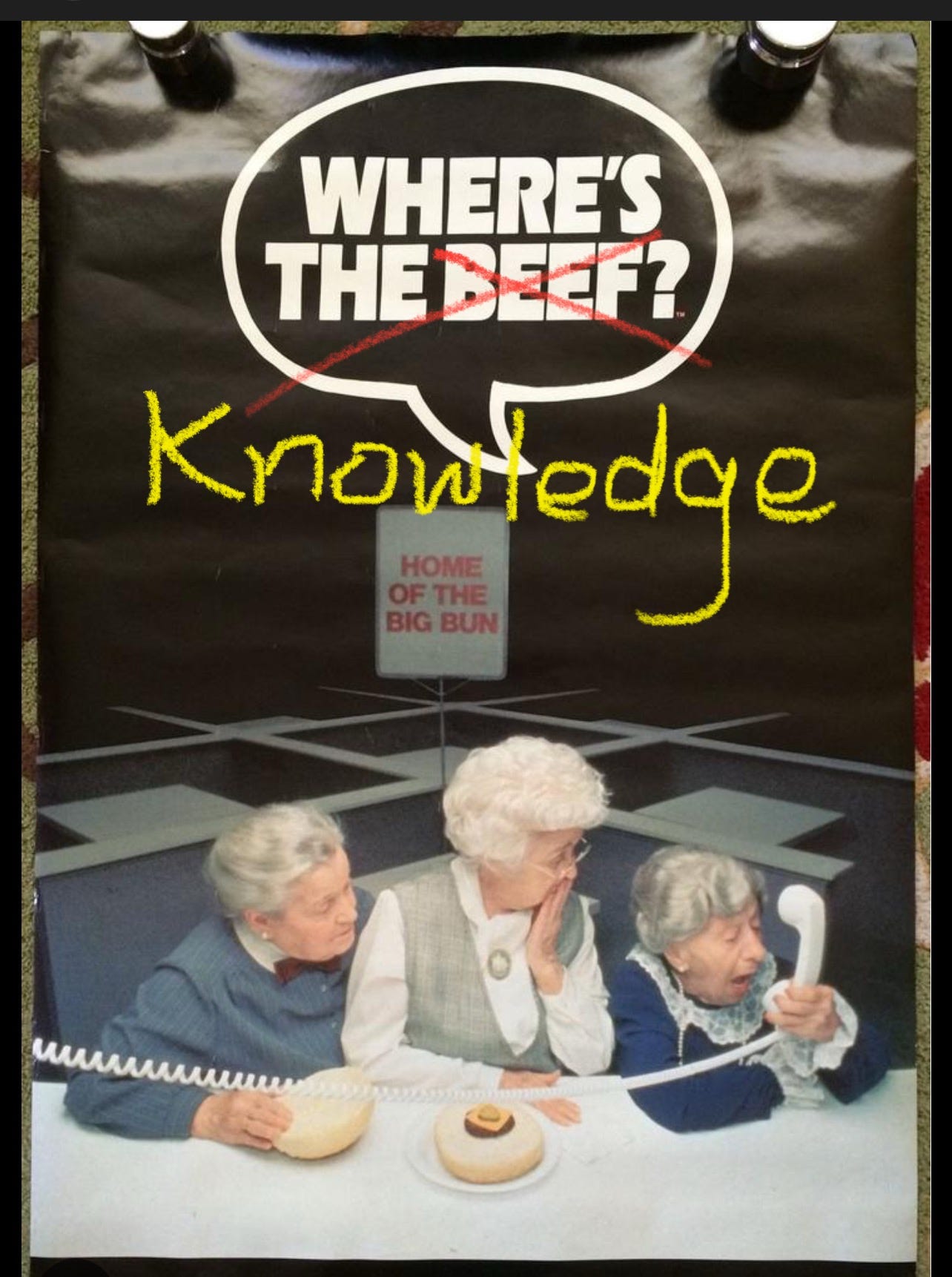

In the classic Wendy’s commercial, Clara Peller famously looks at a burger with more bun than meat and asks, “Where’s the beef?” For whatever reason it became a super popular catch phrase in the 1980s. My older sister even has a purple and white striped night gown with the phrase on it when she was 10. That then got handed down to me.

And now, 40 years later, I’m asking, “Where’s the knowledge?”

I am guilty of the exact thinking that may have led us to where we are. Bloom’s Taxonomy and Webb’s Depth of Knowledge both place factual knowledge at the lower levels of thinking. Not arguing there. There’s a sense that spending time on factual information is a waste of time. And the case can definitely be made that assessing factual information is a waste of time. Identifying factual information as the goal and end of learning is quite problematic for a bevy of reasons. Memorizing facts to regurgitate them on a test and then swiftly forgetting those facts is a total waste of time, particularly when I can very easily use various resources at my disposal to find those facts written and stored for everyone who can read English with access to the internet. (Note my sarcasm: Access to this information is neither ubiquitous nor equal.)

So, teaching has largely focused on “higher order thinking skills” assuming that students are getting knowledge by learning how to think. Information is meant to be discovered by thinking deeply about ideas.

Now read this quotation (probably twice) from John Sweller, who was on Season 3, Episode 1 of the Knowledge Matters Podcast.

“We don’t need to teach people how to solve problems; we’ve evolved to solve problems. We do need to give people information because of it’s an enormously efficient way of learning something. [. . . ] We need to teach people by providing them with information.”

Wait…what?

Sweller is referring to a theory popularized by David Geary. Geary draws a distinction between biologically primary and secondary knowledge based on how we acquire the knowledge. His claim is that we have evolved as a human species to acquire various knowledge and skills without being directly taught. We can, for example, learn to recognize faces or speak our first language without anyone teaching us how. The same goes for thinking. No one has to teach us how to process incoming information. How we get better at thinking largely has to do with how much knowledge we possess about the information we’re processing. Read more about these cognitive processes in “Reading Misunderstood.”

Reading Misunderstood

My sister recently shared that my niece and nephew tried calamari for the first time, so I asked them what they thought. My 8-year-old nephew said, “I didn’t really like it. I did like the brown chicken, though.” When he couldn’t explain what he meant, my niece came to the rescue and said, “He liked the breading.”

When we’re novices and have less knowledge about a topic or idea, we largely have to be explicitly taught information. There are ways to do this that are more and less effective at developing knowledge, and as Willingham points out in “Ask the Cognitive Scientist: Inflexible Knowledge: The First Step to Expertise,” inflexible knowledge is the first step toward flexible knowledge, which is the type of knowledge that an expert in a particular area has access to. So, we do need to provide information directly to develop knowledge. But, while research does support the need for more explicit teaching when first exposed to information, there is also research that suggests explicit teaching starts to become harmful once a learner has flexible knowledge.

But here’s the rub: We cannot force our brains to develop understanding. We cannot control that outcome. We can hone our skills through modeling, but no one can make us understand—that’s on us and our brains. We can create conditions that will more likely lead to some kind of deep understanding, but we cannot guarantee that deep understanding will occur. Think of it like mold growth. If I create a warm, humid, dark environment and put some kind of natural surface like wood or paper in that environment, mold is likely to grow, but I cannot make mold grow.

But let’s get back to knowledge. So why does providing learners with information and supporting their storage and retrieval of that information matter? If we want learners to be able to think deeply and draw on their evolved thinking skills, they must have knowledge to draw from. That is a condition that we can control. We can provide more information and support for developing knowledge. And having more knowledge is likely to lead students to develop flexible knowledge and deep understanding. As Dylan Wiliam shares in the Knowledge Matters Podcast linked above: “The way to make our students smarter is not to give them practice in thinking, but to give them more to think WITH.” Without knowledge, students are not thinking and learning.

This is important, and it’s fundamentally not the conversation that educators are having right now. And, because of AI, there’s an even stronger push to focus on “durable skills” and things which AI seems to not be able to do. Knowledge? AI has it in spades, so let’s not focus there folks. Kids don’t need it. They have AI!

But guess what! AI is “smart” because not only does it have that information, but it’s able to process that information and engage in what some call “higher order thinking skills” like reasoning and inferring and making connections. AI is getting smarter in exactly the ways we should be educating children—give them vast amounts of information, hone their skills in processing that information using thinking skills they have at their disposal to process it, and ask them to share and use that knowledge as they engage with others and tackle new problems or new texts or new ideas which challenge what they already know to refine it and give it more depth.

In It’s Not Complicated! by Rick Nason, he shares, “As a mathematician Einstein was good, but not great, and most certainly not a genius. As a physicist, however, he has few peers, and for that he is considered a genius.” Expert thinkers in each discipline think differently, and we may not all be adept at thinking expertly in everything, but we sure as hell need access to knowledge so that we may get better at thinking.

In Jamie House’s post, “Philosophy is Saving AI. Can it Save our Schools?” he suggests that we need to help students understand how knowledge is used differently in different disciplines:

“We need to help students recognize different kinds of knowledge and the ways they are constructed. For instance, mathematical knowledge often builds through logical deduction and proof, while historical knowledge is shaped by interpretation of evidence and multiple perspectives. Scientific knowledge relies on repeated observation and experimentation, and artistic knowledge may be rooted in expression, metaphor, and critique.

“In my classroom, for instance, when students study historical events, I prompt them to consider what the emotional experience would be like for the actors involved. During science units, I prompt students to identify the type of evidence behind each claim and whether it's based on experimentation or observation and what its limitations may be. These questions help students move beyond content to a more thoughtful examination of how knowledge is constructed at a conceptual level. How do I know this? What kind of evidence supports it? What assumptions or values are embedded in this claim? How might my knowledge be limited?“

In both examples, the foundation is knowledge. It must be present. It must be taught, and it’s often missing from schools, particularly for our youngest learners who are both primed to gain knowledge and need the knowledge to hone their thinking. I spoke to a teacher who said kids receive absolutely zero science and social studies instruction until the sixth grade in her district. So, any knowledge building about the world has to be done during ELA time, when teachers are naturally drawn to more literature. In fact, according to a study by Kristin Smith Conradi, Craig A. Young, and Jane Core Yatzeck and quoted by Dr. Molly Ness in a podcast: “94% of early childhood teachers choose fiction texts as their read alouds.” So the chances that kids are building knowledge about the world in school is very slim. Where’s the knowledge? It is the missing subject!

I’m so passionate about this that I’m going to start a year of knowledge campaign to coincide with back-to-school. Surely if we tackle this, we can help kids become more knowledgeable, which can then lead to deeper thinking. I’m still working out the details, but I hope you’ll join me! Stay tuned for more—I’ll update details here.

Most cognitive scientists will tell you that concepts are the building blocks of thought. But clearly, that prize goes to content knowledge. Or maybe content knowledge is the sand, clay, and shale.