The System is Teaching the Test

A look at how standardized testing reshapes teaching and learning in ELA

“The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

—Donald Campbell

We created assessments to ensure all students have access to a quality education. But when these tools are repurposed for accountability, they often start reshaping the very thing they were meant to monitor. Instead of supporting learning, assessment systems now distort what gets taught, how it’s taught, and who gets left behind.

The Original Sin of Accountability

Assessment systems were designed with an admirable goal: to monitor and improve educational opportunities for all learners. If every student is to receive a high-quality education, schools must be able to measure effectiveness and demonstrate access and equity. But over time, assessments have become tools of social policy. They are used to allocate funding, hire and fire educators, and label schools to justify reforms or closures.

When that shift happened, the definition of “quality” quietly changed. It bent toward compliance and measurable performances and away from real learning.

The Assessment Tail Wags the Curriculum Dog

Today, many classrooms don’t just include assessments—they are built around them. In too many cases, the test has become a “shadow curriculum” that is, in some ways, more impactful on student learning than the officially adopted curricula.

Teachers are asked to align instruction to standards and benchmarks not as guides for rich instruction, but as blueprints for the test. Curricula are written to maximize test performance. And schools are judged on the numbers. The result? The assessment tail is wagging the curriculum dog.

What was meant to serve as a tool for improvement is now driving decisions that narrow both teaching and learning.

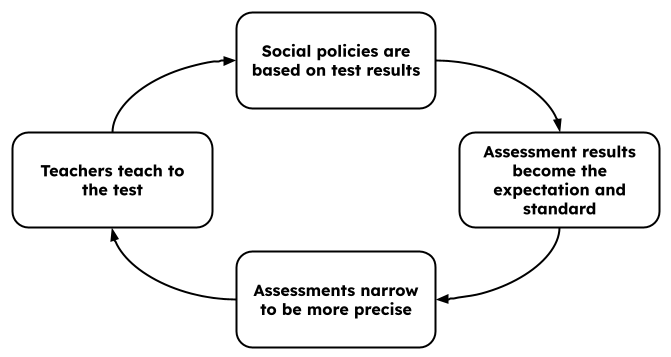

The result is a system that destructively interferes with itself.

What Gets Measured Gets Taught

Summative assessments, originally intended as rearview mirrors, now function as GPS. The desire to predict how a child might perform on an end-of-year test earlier in the year so as to intervene and get the child “back on track,” means that even formative and interim assessments are often designed to mirror high-stakes tests. Teachers feel compelled to prep students for the test or they are so indoctrinated in this view that they don’t recognize what they aren’t teaching. Either way, their instruction is reduced to the kinds of skills and content that are easiest to measure.

The implicit message: “If it can’t be measured, it doesn’t matter.”

See my post about “The Streetlight Effect” for more on this idea.

In ELA: Standards ≠ Comprehension

This is particularly damaging in English Language Arts. When assessments are built around standards, teachers are led to believe that teaching standards is the same as teaching comprehension. But comprehension is not the ability to answer a multiple-choice question about the main idea. It’s the deeply human act or process of constructing and integrating a mental representation of meaning. The standards that we’ve identified are really only small clues into what is actually happening in our brains to make sense of what we read.

Most standards are only proxies for this process. Yet the push for measurable outcomes has led to comprehension instruction being built around isolated questions that may or may not align with the actual meaning of the text, and they rarely build toward deeper understanding.

Ironically, I believe that comprehension, which most classify as the focus of ELA classrooms, can be assessed more authentically in science and social studies than in ELA. In science and social studies, students must use their comprehension to make connections to build knowledge, explain concepts, or draw conclusions and express evidence-based opinions. They are applying their knowledge and associated thinking skills to generate new knowledge about relevant topics. When students read about ecosystems and explain cause and effect or interpret a historical document to understand motives, they’re demonstrating comprehension.

Measurement Distorts Instruction

Assessment systems that are in use across districts and states nationwide are potentially harmful to learning anything other than what can be measured in traditional item-response assessments. Because traditional reading comprehension assessments measure comprehension sub-skills independently (e.g., main idea, character motivation, inferencing), ELA teachers often similarly break their instruction up into sub-skill interactions. While the skills and knowledge which are testable may correlate mathematically to broader abilities, teaching discrete sub-skills is not usually the most effective way to generate knowledge and understanding.

Instruction becomes atomized. Fragmented. Practice is focused on what will show up on the test, not what builds a strong, thoughtful reader.

The Cultural Cost of “Neutral” Tests

Even the design of most assessments contributes to the problem. To ensure fairness and “pure” measurement, test designers often remove any contextual variables and cultural variance as much as possible. For example, for reading passages, they try to find passages that don’t require any type of specific knowledge or experience to understand it. But reading comprehension doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Understanding the contextual and cultural aspects of assessment items is critical to understanding student thinking. A critical part of comprehension is knowledge, which is shaped by what students have read and experienced throughout their lives. This cannot be factored out without consequence.

When we strip assessments of context, we distort the very thing we’re trying to understand. Worse, we introduce bias. Since knowledge is culturally embedded, we end up privileging students whose knowledge aligns with the assumed norm, and disadvantage students whose cultural or linguistic context is different.

Learning and reading is a social and cultural activity. When we disintermediate context from learning, we essentially remove an important portion of what learning is. If a test ignores what a child brings to a text, it’s measuring distance from the norm rather than comprehension.

What Students and Teachers Lose

The pressures of evaluation and performance that come with assessment culture also change how students express their thinking. Once a task is labeled an “assessment,” students begin performing for evaluation, not for learning. This can create anxiety. Sometimes, the pressures are so great, it is paralyzing for students and they come up blank and disengage. Many will conform to what they believe the test wants from them, like answering short-answer questions in a RATE format1, which can limit students’ thinking. We cannot be certain that we’re getting a true and accurate picture of what students know, especially for students who are more likely to feel judged or uneasy by formal assessments.

Meanwhile, in many cases, educators at all levels also have trouble taking real action on the current information they are getting from formative, interim, and summative assessments. The focus on and use of data as numbers in the assessment space often distorts the purposes and uses of assessments. While providing numbers for state- and district-level educators can provide some summary-level statistics that can be tracked for funding, general programming, or management decisions, even these uses can be distorted. Some states offer formulas for improvement and award more points for accountability based on subgroup performance, which results in a gamification of data. System-level administrators often pressure teachers to focus on the performance of particular groups of kids at the expense of others.

I have found that instead of more numbers and scores, teachers are better served by having access to the items and related passages or stimuli to analyze responses and better understand their students. Without access to this information, teachers and school leaders become focused on increasing scores by any means necessary, often at the expense of actual learning.

So What Can We Do?

I’m generally pessimistic when it comes to accountability-driven assessments. I doubt they will even stop distorting the systems they’re intended to support. As Campbell warned, the more we rely on a measure for decision-making, the more likely it is to corrupt the process it’s measuring.

But I’m not without hope. The real measure of the success of an assessment program should be whether it enables teachers to learn something about students’ learning to inform their decisions.

Here are three things educators, curriculum designers, and education leaders can do now to support learning through assessments:

Use assessment data diagnostically, not for evaluation. Focus less on numbers and more on what students actually did and said. If possible, provide teachers access to the items themselves, not just reports.

Build curriculum that prioritizes knowledge-building and meaning-making. Align to learning over standards. Center comprehension instruction around rich, knowledge-building text sets. Provide a robust classroom library so that as kids want to learn more, they have access to more texts.

Advocate for assessments that reflect real learning. While we didn’t set out to build a system that teaches to the test, we’re there now. Let’s figure out how we can measure what really matters. AI tools might be able to help to surface insights that are too complex for traditional systems. If used wisely, AI could help us analyze patterns in student thinking, offer real-time feedback, and even create more individualized assessments that respect context and value knowledge. The challenge is making sure we use AI to deepen learning, not just to make our flawed systems more efficient.

A Secret Worth Knowing

When we measure skills and standards, we are measuring products, but comprehension isn’t a product. It is the cognitive process of constructing and integrating meaning. One solid way to know what children understand is to see how they use their understanding to connect and explain ideas in new, related texts.

A Question Worth Pursuing

How can we know if children are comprehending texts if we never ask how they’re making sense of them?

Next Steps Worth Taking

Share this post with someone who advocates for standards-based assessment.

RATE format: Restate the question, answer the question, text evidence, explain or elaborate